Welcome to the e-reputation economy

Proof through peers: an influence lever extending across the web.

The battle to keep consumer attention by using statements from “trusted third parties” is certainly not new. What is new is that it’s not really taking place on the same playing field, or with the same means. Facebook, Google, Zynga, Spotify Amazon eBay, PayPal, Yahoo…all these brands owe their exceptionally rapid global success to word-of-mouth.

Their economic model is largely based on their virilisation potential: the VCs and financial analysts give them a lot of importance. Joining the top global brands in a couple of years without massively investing in advertising space purchases is the strength of internet brands.

If we add a very low marginal cost – a new user of a platform only costs a couple of cents a month, we can better understand why the stock market entry of Facebook interested so many.

In 2011, Robert McDonald, CEO of Procter & Gamble, decided to lower his advertising budget by $10 billion annually because “Facebook and Google can be more efficient than traditional media.” A quiet but important signal, not of the end of traditional advertising, but a readjustment of brand priorities.

Investors are showing more interest for projects for services based on peer-to-peer exchanges.

If the term still makes reference to companies from the first internet bubble, such as Napster or Kazaa, today, “peer-to-peer” start-ups are centred around supplying a large range of services from person to person.

The disintermediation, which is in fact a reconfiguration of exchanges, is already at work in many fields, with the idea being the decentralisation of transactions and the circulation of information, rather than concentrating them in the hands of a central hub or a handful of experts.

All the major internet success have a dose of peer-to-peer and disintermediation: Amazon has always offered reader comments, which is a way of avoiding guidance from editors. Google offers everyone the opportunity to buy advertising without having to go through an agency.

Consumer advice sites like ciao-fr “bypass” associations for consumer protection. PriceMinister connects individual buyers and sellers or professionals with goods on sale, which were hard to acquire previously…

The immersion into a world that is totally virtual is no longer a long term prospective, but rather a medium- and long-term strategy. With regards to established e-sellers, such as Amazon, it is possible that their growth to come will be reduced by their lack of physical distribution.

One of the main characteristics of a good business model on the internet is its capacity to reduce transaction costs by reducing the number of intermediaries (and sometimes that service that comes with it…)

In fact, the development of use around social networks and mobile internet has created a favorable context for the appearance of a multitude of new “peer-to-peer” services. Where here is a potential gain for the buyer and the seller, there is an opportunity for a new service.

In this universe of decentralised exchanges, spread out and sometimes relocated, a central piece is nonetheless missing so that currently marginalised practices become more generalised: what credit can we give to the eBay buyer or seller?

Is its consumer trust transferable to PriceMinister? What exchange history does the buyer or seller have? How do we talk about them, what is their reputation? How can we avoid spending too much time evaluating their reliability? Etc.

Giving our online reputation a number: what do we want to measure ?

Lacking sufficiently shared indicators, recognized and well established, marketing practitioners have had the tendency to consider as marginal the impacts of “internet buzz” on the behaviour of consumers. We recognize that the wide-spread use of the terms e-reputation, influence, popularity, followers, fans, etc., does not really help understand this new phenomenon. .

But several studies and research papers have shown new insights about the influence of digital media on our daily behaviour.

Dina Mayzlin and David Godes, respectively Professors and researchers at Yale and the University of Maryland, researched the influence of online conversations, over several years, on TV show audiences. Their conclusions brought important insights about the nature of e-reputation: according to them, entropy and dispersion are much more pertinent indicators than the number of citations.

In more operational terms, what counts above all is not the quantity of citations but the potential for virilisation of a piece of information. The more it is taken up and disseminated, the more its impact and influence will grow.

In other words, the repeated media use of information on hubs with large audiences is not a sufficient indicator of its impact or its influence. Rather, it is its capacity to generate its own network of links that will have a positive or negative effect on the perception of the reputation of brands, organisations, or personalities.

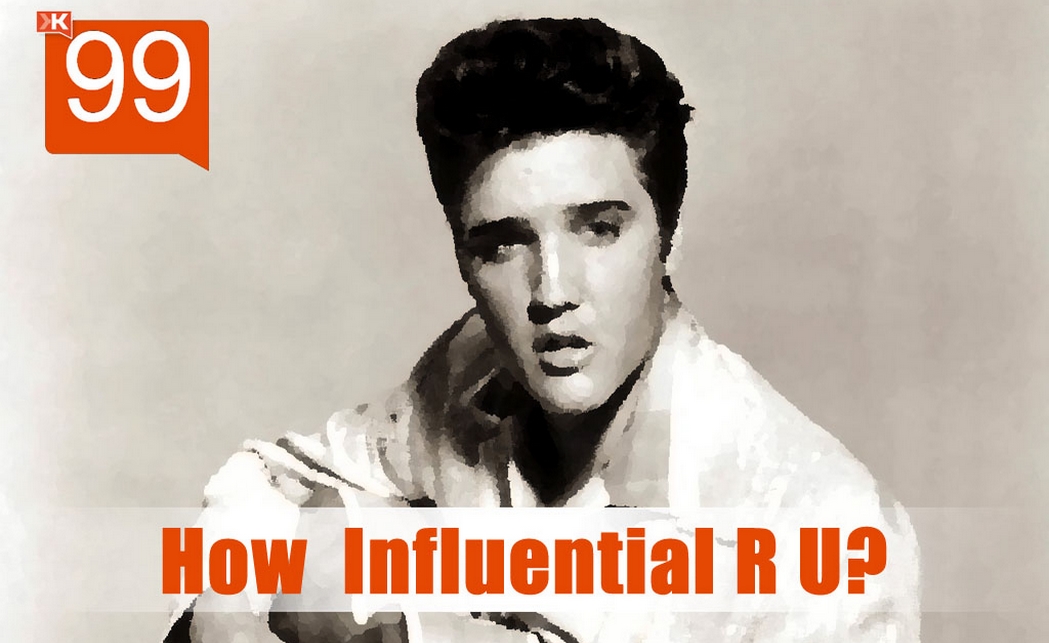

Klout: a contested algorithm for measurement.

Klout measures online influence by tracking people, brands, and organisations on social networks and by analysing their relationships to produce a score of 1 to 100.

According to Joe Fernandez, its CEO, Klout scores are used in many ways, from hotels that offer your higher quality rooms when you reserve online to credit card companies that offer you specific bonuses based on your Klout score.

Of course, the more you are virally influential, the more you can benefit from particular conditions. Klout announced that it receives 7.5 billion monthly searches from outside companies to obtain this information. We are still far from the billions of daily searches on Google, Facebook or Twitter, but the company has only been around for 4 years.

Highly criticised, the Klout score calculation method was revised in November of 2011. Additionally, each person can now request that their personal profile be deleted from the Klout base, a profile that can be created without your having requested it…

Klout defends this attack on personal privacy by arguing that all the data that they collect from social platforms are information that each one of us has consented to have published.

Beyond the rather odd adventures at Klout’s beginning, we can well see that our e-reputation, far from being a hyped up gadget, represents both a personal and collective issue for brands and organisations. Not playing the game is an option, but we bet that few brands can make this choice.

Brand image, rather structured, quantified and relatively controllable, is being superseded to the concept of e-reputation, which in one stroke enlarges the field of what is possible, both in terms of potential opportunities and threats.